Feminist Art: A Look Into Francesca Woodman

Is our view of Francesca Woodman’s work tainted by her untimely demise? Would words like “ethereal”, “ghostly” and “haunting” still be representative of her feminist art if she hadn’t taken her own life in 1981 at the tender age of 22?

Certainly, her choice of subject – her own body – forces us to view her artistic work through a lens of her own identity and existence. Her prolific and complex collection of photographs, comprised of 10 000 negatives and over 800 prints, include techniques such as long exposures that transform her into blurred, spirit-like shapes. However, the artist as seen through the lens of her camera is often alive, young, full of promise.

But who exactly is Francesca Woodman, and what makes her contribution to the feminist art movement so groundbreaking?

Largely unknown during her lifetime, her photographs were first introduced to the public at a Wellesley College exhibition in 1986, five years after her death.

Woodman’s foray into her artistic passion started with her first photographs, snapped at the age of 14. She was born in 1958 into a family of artists. Her parents, George (a painter and photographer) and Betty Woodman, would later, after her death, dedicate much of their lives as stewards of their daughter’s legacy.

George was the one to give Francesca her very first camera, a 2.25-inch-by-2.25-inch Yashica that she used throughout most of her career. Her first self-portrait depicts the artist in her youth, surrounded by forest, draped in a demure white sundress–whose sheer fabric, which is only noticed upon close examination, contrasts with the innocent clutching of her bonnet strings. Already, she was questioning her place as a woman in the male gaze and in the world.

Already, with her first snapshot, Francesca was trying to find how her body relates to the world around her.

Travelling to Rome and then New York, she was inspired by Surrealism and Symbolism, and some of her thematic bodies of work were born from these influences. From the very beginning, she chose to turn the camera on herself. In this way, her work questioned broader concepts of the self, gender, body image, corporality, and identity. When asked why she photographed herself so obsessively, Woodman said: “It’s a matter of convenience—I am always available.”

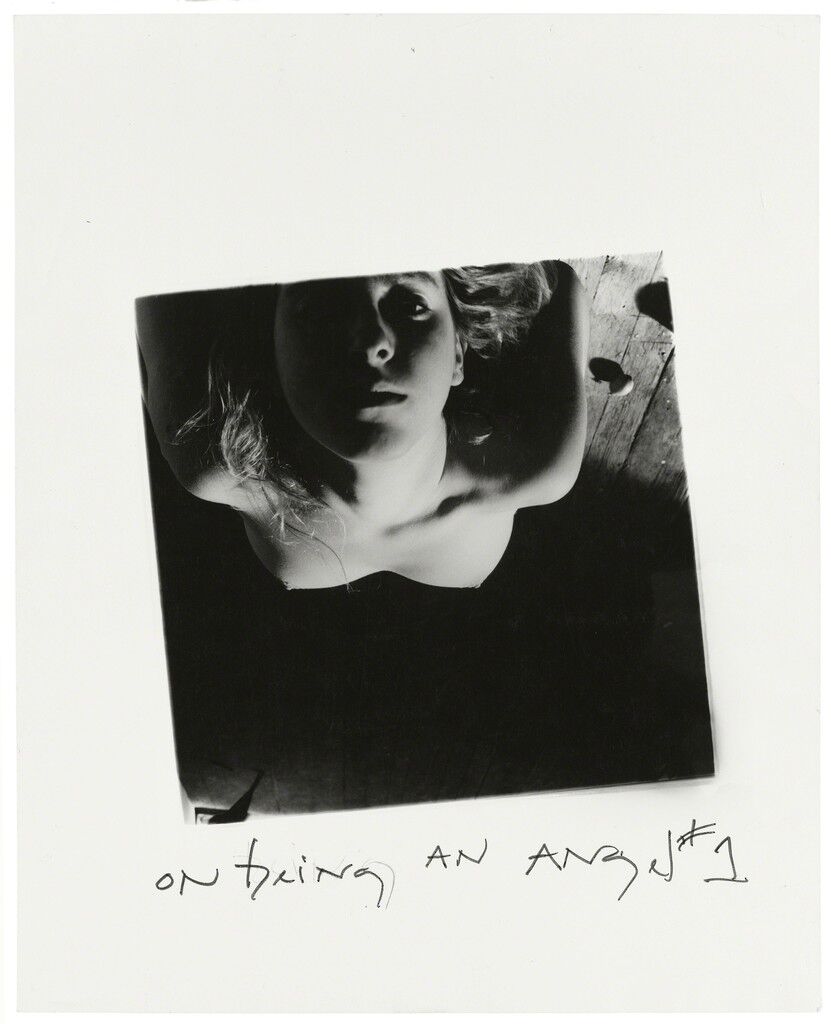

One of her most famous bodies of work centres on angels. Kim Knoppers, the curator of “Francesca Woodman: On Being an Angel” at the Foam Fotografiemuseum says, “the theme of the angel is as a figure that is there and also not there, because it is not human. She is, somehow, always in-between, and this in-between is very important. Woodman’s photographs are about appearance and disappearance.”

“The theme of the angel is as a figure that is there and also not there, because it is not human”

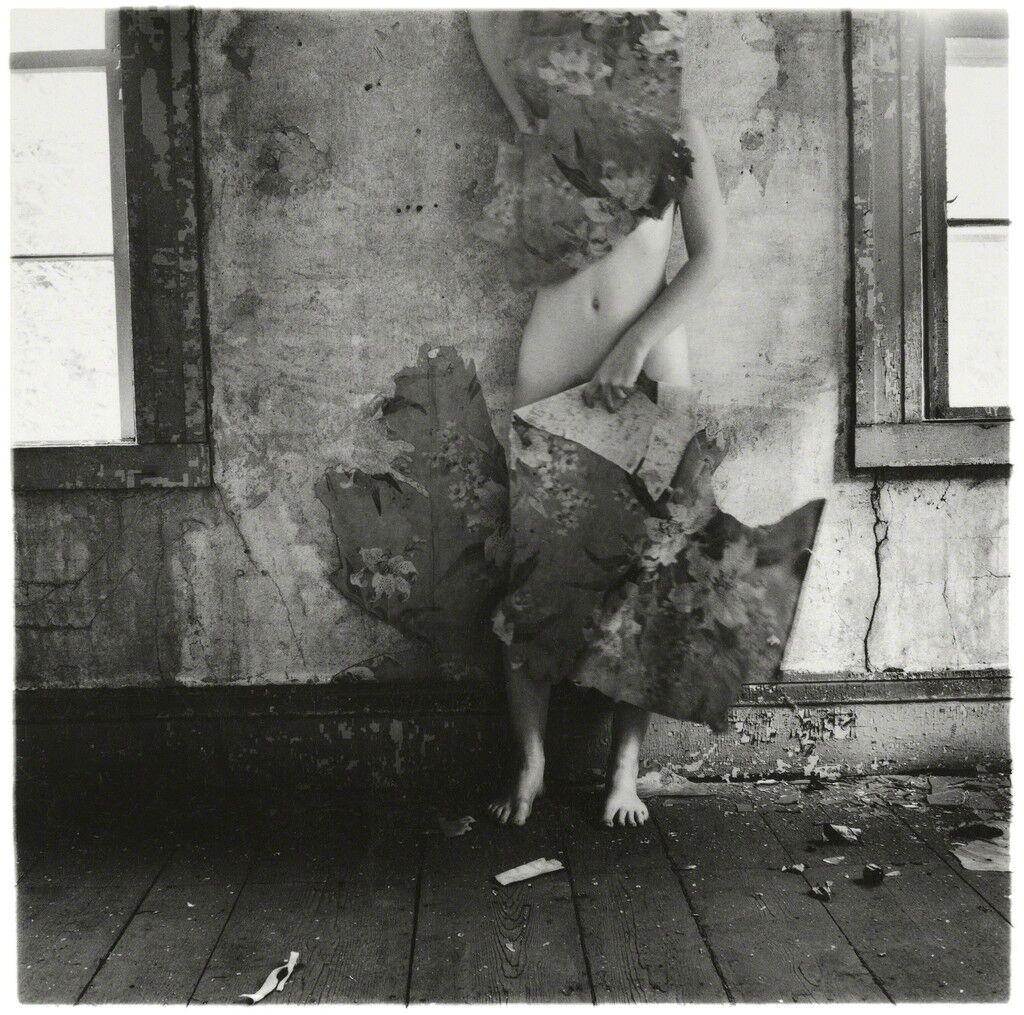

Woodman’s dreamy, erotic body and soul-baring self-portraits are nothing but conventional: they show her representations of the body, especially the female form, often in the nude or in suggestive poses. While not meant to be primarily sexual, they explore gender and self, more specifically how her body relates to the world and her surroundings.

In fact, most of her photographs show Francesca in empty, desolate spaces, her body blending in with her surroundings (hidden behind pieces of peeling wallpaper, half-hidden by a door, etc.)

Woodman’s body often melds with her surroundings.

In the fall of 1980, Francesca attempted suicide, but survived. She received psychiatric treatment and moved in with her parents, who had relocated to New York to advance their own careers. Only a year later, on January 19, 1981, following the end of a romantic relationship, Woodman jumped to her death from the window of a building on the Lower East Side.

The extensive body of photographs that Woodman left behind after her death speaks to a young artist finding her way. She laid the foundation for women to self-inquire by turning the camera on themselves.

Woodman’s feminist photography dealt with tilting the conventions of life, art, and death. In her photographs, she tried to both hide and define herself; in death, she crystallized and ensured her legacy in the feminist art movement.